David & Aaron Stanley

2024 Tour de France Wrap-Up After Week Three:

Point - Counterpoint

David Stanley is an experienced cycling writer. His work has appeared in Velo, Velo-news.com, Road, Peloton, and the late, lamented Bicycle Guide (my favorite all-time cycling magazine). Here's his Facebook page. He is also a highly regarded voice artist with many audiobooks to his credit, including McGann Publishing's The Story of the Tour de France and Cycling Heroes.

David L. Stanley

David L. Stanley's masterful telling of his bout with skin cancer Melanoma: It Started with a Freckle is available in print, Kindle eBook and audiobook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

The premise of this post:

Polymath David Stanley and his son Aaron have sent their individual takes on the 2024 Tour de France after the race finished Sunday, July 21. Neither knew what the other wrote. Aaron's is posted below David's on this page.

David wrote:

There are many ways to rule the peloton of the Tour de France as patron. If you are Bernard Hinault, you rule with threats of physical intimidation. As Jacques Anquetil, you rule with a sense of grandeur and the air of an emperor. But just as no one expects the Spanish Inquisition, whose diverse weapons are fear, surprise, ruthless efficiency, an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope, and nice red uniforms, no one expects a patron whose good sportsmanship and ‘aw, shucks’ attitude are wrapped around one of the greatest aerobic engines ever seen on two wheels, and an assassin’s heart that beats with icy cold.

Tadej Pogačar, the UAE Team Emirates leader, is the patron we didn’t know we needed.

Tadej Pogačar, the patron. Sirotti photo

This has been a stunning Tour. Not all Tours are memorable. Think back to 2019. Egan Bernal wins, the first Latin American winner, and the youngest winner since 1909. But what do we remember? Hailstorms and landslides. Yet this Tour has been marked by a detonation of greatness. Fifteen things (alphabetically) I’ll remember.

2019 Tour de France winner Egan Bernal. Sirotti photo

1. Asshats. See also: social media. People are jealous asshats. When Tadej went on the attack in stage 19, caught, and passed Matteo Jorgenson, I saw an explosion of social media hate that reminded me why sports fans can be incredible jerks. When Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls and the ’60s era Boston Celtics were winning everything, people hated them. No one outside of Manchester ever loved Man U at their peak. Jack Nicklaus was despised for taking down the people's choice, Arnie Palmer. Same with the New England Patriots & Tom Brady. A friend of Italian heritage (H/T Freddie) told me of how his Italian grandfather used to seethe—how Nonno hated Eddy Merckx. Eddy, you might recall, won a lot of races and was not known for gifting stages to anyone.

Let’s have Neal Rogers, ex-editor of Velo-News, put this into perspective. “Mark Cavendish breaking the record for all-time Tour de France stage wins: Marvelous, fantastic, sublime, heroic, historic. Tadej Pogacar winning five stages en route to a third Tour de France victory: Questionable, dishonorable, arrogant, short-sighted, greedy. Make that make sense.”

Reddit, Threads, Twitter, FB – all over the sport-a-verse cycling fans were screaming about how Tadej had ruined the Tour, how he wasn’t sporting, how he was a selfish jerk. That, of course, is grotesque bullshit. First off, Tadej is a highly paid professional. He is paid to win races and get his sponsors as much face time as possible with the world. He is not paid to gift riders stage wins. We don’t see this “gifting wins” in any other world sport. Hell, most of you probably don’t let your kids win at Monopoly or ping-pong. Did any of Sepp Kuss’s teammates gift him anything at the 2023 Vuelta? Who the hell wants a gift, anyway? Pas de cadeaux, mates. Pas de cadeaux.

2. Cheating. Is something going on? Maybe. We’ve all seen this before and we’ve earned the right to our skepticism. The cheating drumbeats were loud when Tadej, and several others, all raced the Plateau de Beille at record speeds and destroyed Marco Pantani’s 26-year-old record. We all know that Pantani was doped with enough EPO to treat an entire cancer ward’s worth of chemo-induced anemia, but does that mean so were Tadej and his flying cohorts?

Jonas Vingegaard climbing to Plateau de Beille. Sirotti photo

No, it does not. There are plenty of scholarly pieces out there that detail the mechanical advantages 26 years of technological advances have given today’s peloton. I’ve ridden dozens of race bikes since I started racing in 1979. A 2024 pro bike is as far removed from Pantani’s 1998 bike as my first real race bike, a 1979 CCM Tour de Canada, was from the bike ridden by Louison Bobet when he won the 1953 Tour d France. According to a site that measures rolling resistance, a modern, tubeless race tire is 9-12 watts more efficient than the race tires of 1998. That doesn’t include the aero advantage of the tire/rim interface, the aero advantage of the modern wheel, the ceramic bearings, the airflow between wheel and fork blades, the energy retained due to the stiffness of the rim-spoke-hub combination, but simply the improvements in treads and materials which decrease the rolling resistance dramatically. Another site crunched the numbers and determined that a modern wheel, in total, is anywhere from 35-50 watts more efficient than Pantani’s.

What else is markedly more efficient? The modern frame and cockpit. Chains and chain lubes. Oversized pulleys. Chainring and pedal and shoe and clothing and helmet aerodynamics. Electronic shifting—you no longer scrub off speed as the chain clicks into location as it does with human shifting. Don’t forget, Tadej is a far more aerodynamic rider than Marco. Pantani, to quote Paul Sherwen (we miss you, Paul) is “all over his machine!” He had terrible form, always in and out of the saddle, bouncing around, and he created an immense amount of human drag. Tadej, (again to quote Paul), “is locked into his machine.”

Marco Pantani on the attack in the 2003 Giro d'Italia. Sirotti photo

These are not marginal gains like bringing your own pillow from home. These gains are measurable and significant. If scandal does break out, and we learn that hijinks are afoot at the Team UAE Emirates bus, I promise to be the first to admit I was wrong. While we pile on the UAE lads, let’s step back and note that if UAE are up to something, so are the fellows from Visma-LaB. Consider this stat from Orla on The Breakaway, which was shared to me from the kind people at Write-Bike-Repeat:

Amazing stat from Orla on the Breakaway, regarding the rivalry between Tadej and Jonas: in four TDFs—84 stages—their accumulated time is separated by just 1:25.

Four Tours. Roughly 82 hours each. A total of 328 hours of racing. Just 85 seconds separate these two young men.

You won’t let it go? The lack of physical evidence is noteworthy. As I said, if I’m wrong, you’ll read my mea culpa here. Boy howdy, I hope I’m right.

3. Richard Carapaz. Polka dots suit him. The Ecuadorian is the definitive plucky rider. With an impressive palmares, he is the first cyclist to achieve an Olympic road race gold medal and a podium finish in each of the three Grand Tours. He ignites every race with serious climbs afoot. He took the yellow jersey after Stage 3, and became the first Ecuadorian rider to do so. He went on to win Stage 17, as he crossed the finish more than 7 minutes before Pogačar, who took back the maillot jaune after Stage 4. By winning his stage, he became the first Ecuadorian to win a stage at each of the Grand Tours. Simply, he races with passion and grinta and exuberance. He’s fun to watch.

Richard Carapaz won the polka-dot jersey. Sirotti photo

4. Mark Cavendish. He didn’t quit. With Tour stage win number 35 in his musette, it would’ve been easy for him to bail during the brutality of several mountain stages. But he did not. He brings honor to himself and to his 35 Tour wins and his total of 165 professional victories with his combativeness. You saw him on Saturday, in the last few km of his last road stage in his last Tour de France, the 14th Tour in his career? Waving, smiling, soaking it in. Then, as he crossed the line, he broke into tears into the arms of his teammates. The 39 year old Cav is, as he has always claimed, “a really good bike racer.”

Mark Cavendish finishes stage 21 of the 2024 Tour de France. Sirotti photo

5. Biniam Girmay. Green, even Skoda green, looks good on him. As I wrote last week, he is an extraordinary national hero. Bigger than Lionel Messi in Argentina, bigger than peak Tiger Woods here in the States. His feats in this year’s Tour will inspire an entire generation of young people in Eritrea for the next ten years. If I ran a pro squad, I’d put together a load of bikes, a bunch of coaches, and travel through the Horn of Africa in search of 30 teens whose parents are willing to move with their children to Europe to live, school, and train. Out of that group, I am convinced, will come the first great generation of Black African cyclists and certainly the first Black African Grand Tour champions. Biniam said that when he saw Daniel Teklehaimanot take the polka dot jersey very early on in the Tour back in 2015, it showed him he could do it too.

Biniam Girmay takes home the green points jersey. Sirotti photo

6. Ben Healey. I love Ben; unabashedly and openly. His aggression and combativity were second to no one in this year’s Tour. He was always on the attack, and in a year with a lesser version of Tadej, he might well have won his stage.

Ben Healey gritting his teath as he time trials in stage 7.

7. Matteo Jorgenson. I love this guy, too. I was gutted for him when Tadej blew past him with just a wee bit to go, but truly, didn’t everyone, including Matteo as he neared the top of Stage 19, realize that he would most certainly get caught by the soaring Pogačar? Matteo, with a skidding crash, still earned a 4th place finish in the final TT, 2:08 behind Tadej. He finished the Tour in 8th place on GC, only 26:34 behind the yellow jersey. A remarkable accomplishment for the 25 year old from Walnut Creek.

Matteo Jorgenson racing the brutal 19th stage. Sirotti photo.

Matteo showed the world that while his Visma | Lease a Bike team leader Jonas Vingegaard perhaps missed Sepp Kuss, the 2023 Vuelta winner out with Covid, he was no slouch, and clearly equally adept at working for JV. He was more than an outstanding teammate on the road. He was a true teammate on the team bus, too. Said Matteo to JV after the heartbreak of stage 19 to Isola 2000,where Jonas conceded he could not beat Tadej. “Hey, I’m proud of you,” Jorgenson said. “You gave everything, that’s all that matters, really.” That’s a stand-up guy you want on your team. Kudos, MJ, man. Kudos.

8. The Pentagon of Cycling. Learned cycling folks spoke of how it was nearly impossible, in the 21st century, for a rider to do the Giro-Tour double. They were right for 23 years. I propose a new standard; the Pentagon of Cycling. Is it possible for a rider to win the Giro, TdF, Olympics, Vuelta, and the Worlds? In a single year? Probably not. In a career, quite possibly. But in 2024, don’t say impossible.

9. Matthieu van der Poel. Remember back in my preview piece when I said that Astana had hired the world’s best lead-man, Michael Morkov, to lead Cav to the promised land of 35 stage wins? Yeah, I was all kinds of wrong. Morkov is terrific, but it’s really MvdP that owns the title of the world’s greatest lead-out man these days. What he did for teammate Jasper Philipsen as JP took 3 stage wins on stages 10, 13, and 16 was exceptional. It was clear to me that MvdP was using this race to build for the Paris Games and I’ll be shocked, yes shocked, if MvdP doesn’t stand on the top step of the Paris podium. His power, fitness, and race-reading ability are a step above the rest of the world in a one day hilly race.

Mathieu Van der Poel in the world champion's rainbow jersey racing stage nine. Sirotti photo

10. Nils Pollitt. Joseph Bruyère was the super lieutenant of Eddy Merckx. Indurain was the power behind the greatness of Delgado. Sean Yates. Tim Wellens. Tim DeClerq. Every great team has a guy who can sit on the front at 45-50 kph for ten minutes, roll off for 1 minute, and then go back to the front, and repeat the cycle for 100 km. UAE Team Emirates’ Nils Pollitt is that guy. For this race, we’ve also seen the 1.9 meters, 81 kg guy go up the hills well, too. An immensely strong rouleur with a solid palmares in the cobbled, one day classics, the 30-year-old German is simply indomitable.

Nils Pollitt racing in stage three of the 2021 Etoile de Bessèges. Sirotti photo

11. Christian Prudhomme. The Tour, you might know, has two starts. The first is the roll-out, known as the départ fictif. It’s a neutral zone, no riders may pass the lead vehicle, which is generally run at 30 or so kph, and runs for several km from the village départ until out of town. It is a start parade. Outside of town, the actual start, the départ réel takes place. At that moment, early every afternoon, race director Christian Prudhomme rose up from the vehicle through the sunroof to wave a flag like a sunflower growing up into the breeze. As the sunflower Prudhomme unfurled its leaves, the stage was on.

2018 Tour de France, from left: Bernard Thevenet, Bernard Hinault and Christian Prudhomme. Sirotti photo

12. Race Radio. The UCI will run several major races later this summer without team-car/rider radios. Whether that will affect the Tour in 2025 or beyond is yet to be told. But I speak of the race radios today. We can now listen to the comms between team directors and the riders. Some are broadcast on air. Some are broadcast on the Tour’s official website. At first, it seems quite cool, to peel back that curtain. Then you realize, to listen into the radios is to listen in to workplace talk everywhere. “Hey, can I get a bottle and gel?” “I need to get rid of these gilets, guys.” “Hey, fellas, the road narrows, get to the front, okay?” “Okay, guys, we gotta be at the front here. Keep protecting "Star Rider" and let's get someone in the break early.” Plus, the inevitable workplace bitching about a colleague - “Jeezus, where the fuck is Wolfgang? Get his ass up here to take a couple pulls. I been on the front the last 8k. Fuck, where is that asshole?”

13. Remco. Youngest man to win stages in all 3 Grand Tours. A kid with a sense of humor. A kid not afraid to offer an opinion: “He has no balls” in the heat of battle. A kid not afraid to give props to another rider and reach out with a fist bump. Also, a kid who can crush the GC and the time trials. He’s really really good, and fun to watch. As this bit is written on Saturday as I watch stage 20, I think he takes the Sunday TT. I hear it’s nice in Nice this time of year. (He didn’t win the TT. Whoops-a-daisy.)

Remco Evenepoel won the Young Rider Classification and its white jersey. Sirotti photo

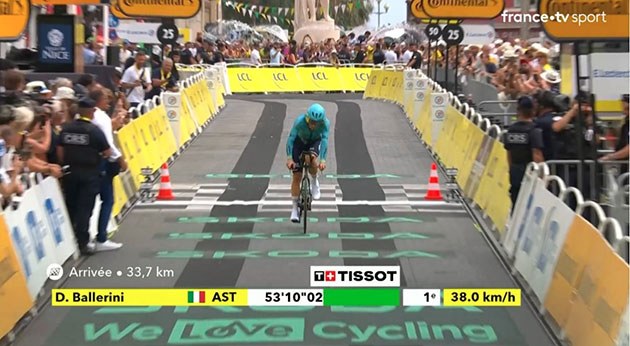

14. Unsung Hero. Kudos and chapeau! to Davide (no relation to Classics great Franco) Ballerini. The Astana man has several major wins to his palmares. A professional since 2017, he has won the 2021 Het Nieuwsblad, the 2022 Coppa Bernocchi and a gold medal in the road race in the 2019 European Games. But for this race, he had one job, and one job only-make 100% certain that Mark Cavendish survived the toughest days in the mountains so that Cav was able to start the closing TT on stage 21. A lot of work went into Astana’s Project 35 and I feel comfortable saying that without Ballerini’s selflessness, the odds of the Tour’s Stage Winning Champion seeing the finish drop down to about 20%.

Davide Ballerini finishes stage 21.

15. Jonas Vingegaard. 100 Days Ago, Vingegaard’s life changed. A terrible crash at the Tour of Itzulia left the Dane with a broken collarbone, fractured ribs, a fractured scapula, and a collapsed lung. It’s terrifying. As he lay in the ICU, pumps running and tubes everywhere in his body, he felt he might well die. There are few worse feelings. In 2012, I was admitted to the ICU with 14 blood clots in my lungs, any one of which might break free, travel to my heart, and kill me. I was scared to go to sleep because I thought I might not wake up. Jonas, just 100 days ago, was in a similar state. He checked out of hospital on April 16, and on July 21st, he stood on the 2nd step of the podium in the world’s most grueling athletic event. That is the equal of Tadej’s majesty as he claims the Giro-Tour double.

Jonas Vingegaard leading Tadej Pogacar up the Col de la Couillole ner the end of stage 20. Sirotti photo.

Yes, the equal. In sport, wins matter. In life, wins look different.

Vive le France! Vive le Tour! vive les Jeux Olympiques!

Aaron wrote:

This year’s Tour de France had drama, monotony, excitement, joy, heartbreak—in short, just another edition of the most important race on the cycling calendar. Here are a few thoughts on some of my favorite storylines of the 2024 iteration of la grande boucle.

The Green Jersey Fight

It was hard to decide, going into the Tour this year, what the battle for the green jersey might end up looking like, but it feels safe to say that virtually no one anticipated the eventual outcome. Jasper Philipsen seemed the overwhelming favorite as the fastest man with the best team around him; Arnaud de Lie came to the Tour fresh off winning the Belgian nationals with an explosive finish; Mads Pedersen and Dylan Groenewegen were poised as ever to fight for stage wins; Mark Cavendish was once more seeking his white whale, the 35th stage win of his career.

Jasper Philipsen wins stage 16. ASO photo

Who, then, expected it to be Eritrea’s Biniam Girmay who would take the race by storm? He became the first black African to win a stage and wear the green jersey, and he and his Intermarche-Wanty team saw no reason to give it up easily. The battle that ensued between Girmay and Philipsen across intermediate sprints and stage finishes alike was a fierce one, and while Philipsen certainly got his, finishing with three wins, Girmay would be the ultimate victor, winning three stages of his own and wearing the green jersey into Nice. This was a true ascension for Girmay, and it was clear throughout the Tour how much it meant for him, his team, and everyone back in his hometown of Asmara. It is not every year we the viewers are privy to such feel-good stories, but Girmay’s triumph—to say nothing of Cavendish finally reaching the elusive milestone of the stage wins record—was an easy storyline to root for with an eventual satisfying ending.

Biniam Girmay wns stage 8. Sirotti photo

EF Education First

Possibly the most exciting squad to follow over the course of the race, EF had their share of ups and downs throughout the race, lowlighted by an inability to contest sprint finishes with Marijn van den Berg. Nonetheless, the team earned a day in yellow in week 1, with Richard Carapaz pulling on the maillot jaune after stage 3 based on sum of placements.

Richard Carapaz in yellow after stage 3. Sirotti photo

Though Neilson Powless suffered a broken bone in his wrist during stage 12, he fought onward all the same, remaining in the race and putting forth effort at the front of the peloton day in and day out. Ben Healy and Carapaz spent countless hours in breakaways on mountain days; they toiled away, in Dan Jenkins’ words, like dogged victims of inexorable fate, doomed to watch the likes of Pogacar, Vingegaard, and Evenepoel motor past them at 7.5 w/kg up the slopes of the highest mountains, saying “good effort lads, we’ll take it from here” as they swept up the stage wins.

Neilson Powless racing on the white gravel of stage nine. Sirotti photo

Finally, though, stage 17 brought triumph to the men in pink. With Charles Wigelius surely in his ear urging “cam on Richie, cam on”, Carapaz dropped Simon Yates and Stevie Williams from an elite group of six to claim the first Tour stage win of his career atop the Superdévoluy climb. For EF, it was the culmination of several weeks of valiant but theretofore unsuccessful efforts, their hard work paying off after days upon days spent in breakaways or working to put their sprint train at the head of the peloton on the flat days. Carapaz would venture forth and take the polka dot jersey the day after, and thanks to his efforts throughout the last ten days of the tour was additionally awarded the supercombativity prize. Despite their early uncertainty, EF were a team that placed the spotlight upon themselves through sheer force of will over the course of the three weeks of the Tour, and they deserve a great deal of credit for everything their racers put themselves through in pursuit of success in any form.

Victor Campenaerts and the Emotions of the Tour

In 2023, Matej Mohoric won stage 19 and won the hearts of fans everywhere with his tearful, heartfelt interview where he expressed the difficulty and cruelty of cycling. In 2024, it was Victor Campenaerts, after winning stage 18, who provided another emotional moment at the Tour, sharing his struggles with contract talks with his Lotto-Dstny team, his altitude training camp prior to the race, and all of the support his extremely pregnant wife lent him in the lead-up to the Tour de France. It was a poignant moment for the Belgian rider who put himself through so much and put so much pressure on himself and finally earned the greatest reward imaginable, and it was a touching reminder of the humanity present in the peloton.

Victor Campenaerts wins stage 18. ASO photo

Cyclists may appear at times like machines, built to push watts for endless hours and repeat for weeks, months, years on end, but hearing from riders such as Mohoric and Campenaerts reminds us all of what is given up to become a professional in one of the most demanding sports on the planet and all that is required from teammates, friends, and family to reach the highest levels of success.

Pogacar: GOAT in the making?

Tadej Pogacar has a career’s palmares through 5 months of racing in 2024 alone. He won Strade Bianche by 2:44; the Volta a Catalunya by 3:41; Liege–Bastogne–Liege by 1:39. At the Giro d’Italia, he won 6 stages and wore the maglia rosa for 20 of 21 days en route to a 9:56 margin of victory and the mountains classification to boot. The Tour de France, though, was his greatest triumph. Despite a gigantic target on his back and challengers including Jonas Vingegaard and Remco Evenepoel gunning for him at every turn, Pogacar put on a performance that can only be described as supernatural. He won six stages, taking his total to 12 in two Grand Tours on the year, including the final 3 in a row, becoming the first non-sprinter in nearly 90 years to win three consecutive Tour de France stages. He beat back all comers, no matter what was thrown his way. He dominated the race with panache, shining resplendently in the maillot jaune for 19 days. (For those playing along at home, that means Pog spent 39 out of 42 days across the first two Grand Tours wearing the leader’s jersey. As one does.)

Pogacar before the start of the 2024 Tour. An incredible demonstration of racing ability was coming. Sirotti photo

There are those who say dominance of this level is boring. But Pogacar makes himself impossible to dislike. He takes such obvious joy in cycling, in competing, in the thrill of the race; he has a smile, a joke, a handshake for anyone he finds himself next to in the peloton. Stylistically, he is a joy to watch, winning with a true sense of style, attacking even when there’s no reason to do so, nothing to be gained, simply to push his legs, to have some fun. The only question left to answer for Pogacar, at merely 25 years old, is how many records can he set? He holds 3 Tour wins and 17 stages, a Giro win with 6 stages, 12 other stage race wins, and 6 monuments. Again, at 25 years old. The sky seems the limit, and it will surely be thrilling to watch him the rest of the way in 2024 as he chases the Olympics and Worlds and beyond into the future. What heights can cycling reach? Pogacar may be the one to teach us.

The route

This year’s parcours came to mixed reviews; there were quite a few unfortunately dull flat days, a polarizing gravel stage, and a range of high mountain stages that were difficult to predict—were some too early, others too late? Would the mountaintop finishes provide the drama we’ve come to expect? In the end, this Tour’s route receives high marks for the latter two, but low marks for the former. Thanks largely to the tireless efforts of Jonas Abrahamsen, the flat stages managed to have at least some intrigue, but for the most part the control levied upon the peloton by the GC teams prevented breakaways from having any success, and while a solution to this issue will be difficult to discover, it’s an area of the race that requires continued work. On the other hand, stage 9 exceeded expectations, providing one of the most exciting and dramatic stages of the entire Tour, and there were countless highlights in the mountain stages; all told, one can consider the race design as a whole largely successful.

Jonas Abrahamsen before the start of stage 8. Sirotti photo

The teams: some quick thoughts

Finishing at the top of the team standings, UAE got everything they came for, with Pogi winning 6 stages and the GC, Almeida finishing in 4th, and Adam Yates in 6th. Juan Ayuso was their lone lowlight in frankly confusing fashion, but otherwise it is virtually impossible to find fault with UAE this year. Visma-LAB had impossible standards to live up to after their ridiculous 2023 season, but Jonas Vingegaard pushed the limits of recovery from injury to finish 2nd overall and win a stage while Matteo Jorgenson raced his way to an 8th place finish. Detractors will consider this an unsuccessful Tour, especially given the underperformance of Wout van Aert, but VLAB is being held to a nigh-impossible standard; all things considered, they must be given credit for what they managed to achieve this year.

Jonas Vingegaard wins stage 11. Sirotti photo

Some teams, on the other hand, vastly disappointed this year. Ineos has seemed a bit of a rudderless ship for several seasons now, and they continued to flounder; Carlos Rodriguez was expected to be a GC threat, but despite his 7th place finish he was never really in the running for a podium spot or stage wins; Egan Bernal continues to struggle on the long road back from injury; the team’s direction, as a whole, seems questionable. They must determine their identity going forward in the calendar and as the years pass by to reclaim their former glory. Lastly, recently rechristened Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe … well. Primoz Roglic crashing out would hurt any team, but when your entire goal is to chase the yellow jersey and your leader goes out of the race for the third time in his last three Tours de France, it’s only going to end up a disappointing year. Jai Hindley managed to salvage a top 20, but there was little to celebrate for a team expected to compete at the head of the race.

Young riders: the future is bright

Remco Evenepoel proved that he deserves all the hype. A third place finish in his first ever Tour de France, the white jersey, a stage win, and proof that he can, for the most part, hang with the world’s best climbers in the high mountains? He set himself apart from the field by sticking with Pogacar and Vingegaard day-in and day-out, and it will be exciting to watch his career as a GC threat develop. Matteo Jorgenson and Derek Gee lived up to expectations with top-10 finishes; though neither won a stage, Jorgenson was highly visible day-in and day-out at the head of the race in the mountains and Gee maintained a steady if unassuming presence in the most important moments despite having little support from his team.

Derek Gee climbing in stage 14. Sirotti photo

Santiago Buitrago managed a 10th place finish, hanging around in all the important days. It was a somewhat disappointing race from Arnaud de Lie considering the hype around him coming into the Tour, but he gets a bit of a pass insofar as this was his debut grand tour. Oh, and as a reminder: Tadej Pogacar? Still only 25 years old. It’s safe to say that cycling will be in good hands for years to come.

Parting thoughts

Year in and year out we avidly follow a group of 180 men on bikes around France. Through cities, across sprawling fields of sunflowers, up mountain passes, their fates provide a dramatic thread wending its way through the doldrums of summer across the world. Whether meeting with triumph or despair at the end of the three weeks of racing, the cyclists who complete the Tour de France have accomplished something incredible. Be it Tadej Pogacar continuing to author a career that will one day assuredly stand among the greats, Mark Cavendish closing the cover on his own book of records, or a seemingly nameless and faceless domestique finishing in the middle of the pack, content with reaching the finale in one piece, it’s impossible to overstate what it means to complete a Grand Tour successfully. Chapeau to all the riders, congratulations to the winners, and cheers to another Tour de France in the books. Vive le Tour!

David Stanley, like nearly all of us, has spent his life working and playing outdoors. He got a case of Melanoma as a result. Here's his telling of his beating that disease. And when you go out, please put on sunscreen.